New Horizons for Chronic Pain Management

The emerging science around the experience of pain in the body.

By: Janine Zoromski, NP

If you follow advancements in medical research and understanding, you’ve undoubtedly heard of chronic pain. Or, if you’re like 50 million Americans, you may be someone who has suffered from it personally.

Pain can be experienced as an unpleasant feeling or sensation of hurting that is often a signal by our bodies that something is wrong. And generally, we can categorize this experience as acute or chronic.

The Difference Between Acute and Chronic Pain

Acute pain typically comes on quickly and lasts a relatively short amount of time (fewer than 3 months). It is often a response to an unexpected event, such as an injury or infection, or an expected event, such as menstrual cramps or labor contractions – and can be resolved with time and/or treatment, allowing you to return to your life as usual after it’s gone.

Pain lasting longer than 3 months, however, is considered chronic. This type of pain can remain even after an injury or illness has been healed, or come on without an associated pain-triggering event. Chronic pain is often linked to conditions like migraines, arthritis, back pain, and fibromyalgia; can lead to anxiety and depression; and interferes with daily life.

What Causes Chronic Pain?

Although the causes of chronic pain can sometimes be obvious, like in cases of cancer or long-lasting illness, they’re more often less clear and far more complex. Emerging neurological science and pain research contributes psychological and emotional factors to causing chronic pain, just as significantly as physical ones.

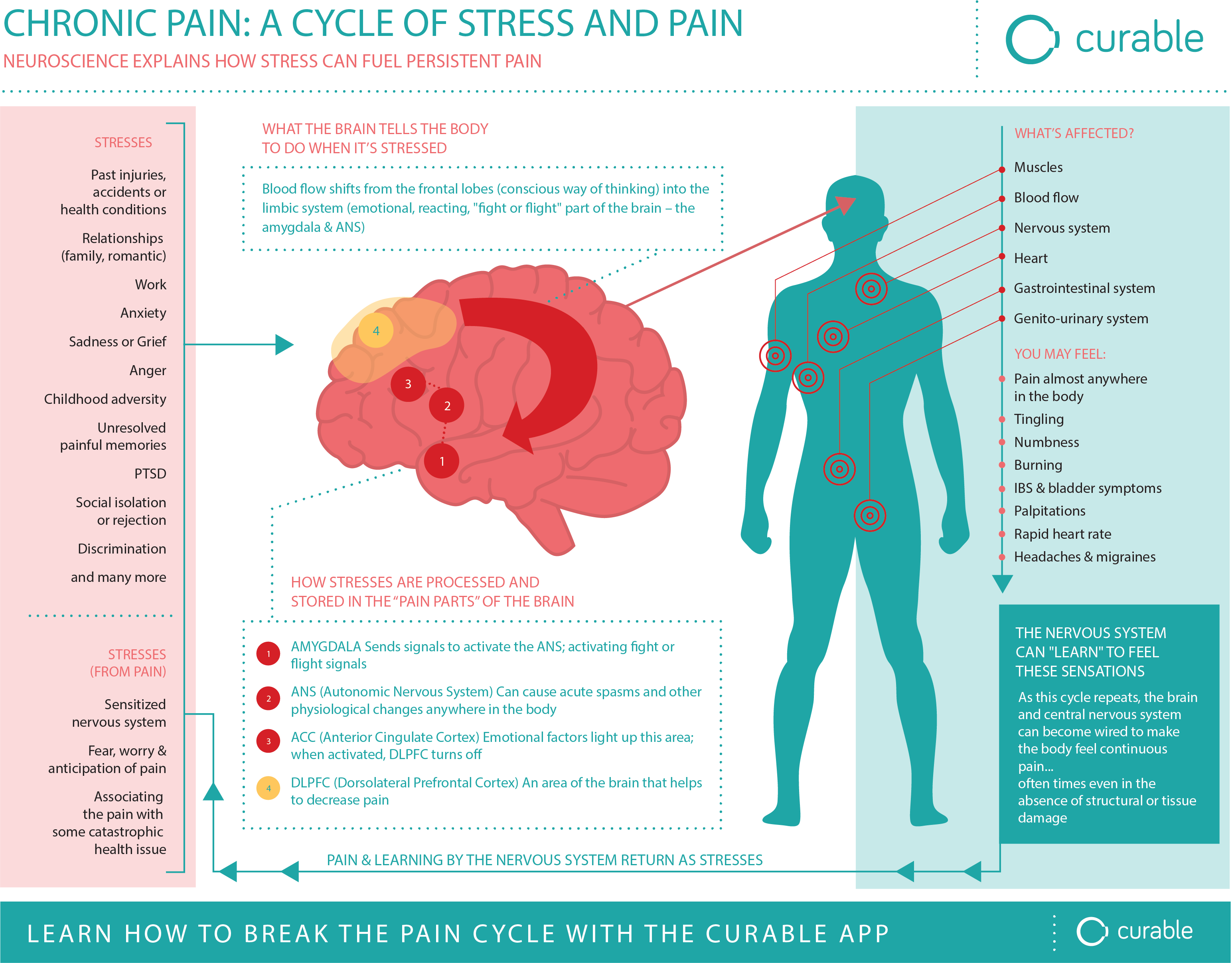

The body’s nervous system is designed to detect and respond to danger. It begins learning this detection and response function in childhood and is continually informed throughout the course of your life. When introduced to traumatic events, health scares, major life changes, or regular stressors from everyday living, the nervous system can become overloaded, over-sensitive, and thus, over-protective – sending the symptom of pain with greater and greater efficiency, with or without a physical-triggering cause.

This phenomenon is called nocioplastic pain, or pain that is the result of the brain misinterpreting or bundling the body’s messages, and understanding them as dangerous even when no danger is present – sending pain signals that are largely “false alarms.”

Nocioplastic pain results from the brain misinterpreting safe messages from the body as if they were dangerous. In other words, nocioplastic pain is a false alarm. Though the pain can be addressed psychologically, this does not imply that the pain is imaginary.

Here are the key factors of nocioplastic pain:

- Emotional state: Psychological factors such as underlying anxiety, depression, fear, post-traumatic stress disorder, and unresolved trauma can significantly influence the experience of nocioplastic pain. These emotional states can amplify pain perception and make it more difficult to cope with pain.

- Sensory: How you experienced the injury or precipitating event can cause the pain to persist even after the physical damage has healed. This suggests that there is a residual abnormal processing of pain signals that continues to fire even though the precipitating event appears completely resolved.

- Social environment: Social environment factors contribute to nocioplastic pain, including stress from work, personal relationships, finances, or work-life balance, and may exacerbate pain symptoms. Inadequate social support, isolation, and lack of understanding from others may also continue the development and persistence of nocioplastic pain.

- Opiate use: Ongoing use of opiates increases the likelihood of developing chronic pain including nocioplastic pain. Opioids are most effective for short-term pain management and long-term use can lead to changes in the nervous system’s pain processing pathways, making the pain more persistent and resistant to treatment.

These non-physical factors can “teach” the brain to be in pain, re-wiring the body’s neural connections to contribute to an ongoing sensation of pain. When someone is taking a high dose of opioids but still reports considerable pain, this is a clue that non-physical factors are contributing to their pain and resolution requires different interventions – not more prescription pain medications.

Treating and Managing Chronic Pain

With comprehensive and holistic treatment methods, the brain can “unlearn” its misinterpreted danger pain response, improving quality of life and decreasing the experience of pain for sufferers – and in some cases, achieving total pain relief.

Research shows that methods like physical and occupational therapy, patient education, mental health regulation, and cognitive behavioral therapy can successfully help the brain to stop this recurring pain cycle.

Chronic Pain Treatment Modalities:

- Physical Therapy / Occupational Therapy – PT/OT methods can improve the body’s structural performance and help the brain disassociate a specific movement or body area from pain.

- Pain Education – Learning about how pain works in the body can help the brain engage in more rational information processing (prefrontal cortex) instead of solely relying on its fear systems (amygdala and autonomic nervous system).

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy – CBT is a form of talk therapy that helps people identify and develop skills to change negative thought patterns (like catastrophizing or thought spiraling) and reactionary behaviors to better manage and cope with their pain over time.

- Addressing Depression / Anxiety – Because similar brain areas are activated with depression, anxiety, and pain, the experiences can get conflated. Treating depression and anxiety can help reduce nervous system overstimulation and non-physical pain triggers that contribute to chronic pain.

- Non-Opiate Medication – Certain medications can be used to help treat chronic pain depending on the cause, such as anti-anxiety medications (like Gabapentin), and antidepressants (like Duloxetine). NSAIDs and Tylenol should only be used on a limited basis under the direction of your medical practitioner because long-term use is associated with adverse side effects.

- Activity – Physical activity and exercise can both reduce our body’s perception of pain, as well as positively impact mental health, with effects like mood elevation, and reduction of stress and depression (conditions often associated with chronic pain).

- Weight management – Since adipose tissue is metabolically active, secreting pro-inflammatory chemicals and being overweight can contribute to your level of pain. Following a nutrient-dense, anti-inflammatory diet can help reduce pain.

- Improved Sleep – interrupted sleep cycles can increase the experience of pain in the daytime, with research showing that one of the most important predictors for pain sensitivity is the number of hours slept the night before. If you sleep poorly, your pain will be worse the next day.

The bottom line is that chronic pain is complex, and should be treated with a multidisciplinary, multi-modal approach aimed at both management and care. Setting reachable goals for improvement, and aiming to increase the quality of life throughout the healing process, can have a profound impact on a patient’s success.

To learn more about Hopkins Medical Group and chronic pain management opportunities, watch the Build a Better Brain Townhall with chronic pain specialist Janine Zuromski, NP, MPH.